By Sylvester Ike Onwudiwe

“The voice of your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground.” These haunting words from Genesis 4:10 remind us of Cain’s dark deed: he killed his brother Abel in secret, yet Heaven heard, the Earth responded, and Cain was cursed—not only for the act of murder but for denying the anguished cry of the slain. In much the same way, Nigeria was forged amid the spilling of Igbo blood.

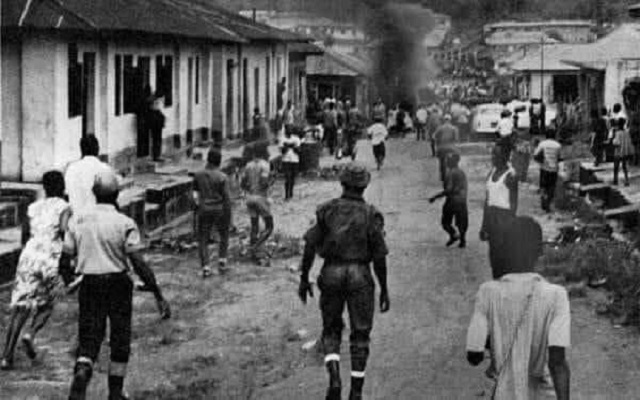

But like Cain, the nation has neither wept nor atoned; it has refused to build monuments to the fallen. Instead, history has been buried beneath silence and lies. Children starved to death in Biafra. Pregnant women were torn apart in Kano. Elders were burnt alive in Zaria. Names erased. Graves left unmarked. Stories left untold. Yet still, the blood speaks.

The Qur’an too forbids unjust killing. It teaches that “If anyone kills a person… it is as if he had slain all mankind” (Surah Al-Ma’idah 5:32). It condemns the shedding of blood without justice and warns that those who do so invite chaos upon the land. Were the Igbos not slaughtered en masse in the name of false unity? Were babies not abandoned to die in the bushes while soldiers danced around food blockades?

What peace does Nigeria seek when it has never confronted the blood it spilled? The Qur’an teaches qisas—restitution—through punishment, truth, or reconciliation. Yet, there has been no tribunal, no apology, no national day of mourning. Only denial. And that denial has bred banditry, Boko Haram, economic decay, and spiritual paralysis.

In African spirituality, particularly Igbo cosmology, blood spilled on the land demands appeasement. Ala—the Earth—is not mere soil but a living being: dynamic, a custodian of justice, memory, and curse. She weeps, she nurtures, and she reacts to blood. An Igbo proverb says, “Ala adịghị echefu ozu”—the earth does not forget a corpse.

Those who shed innocent blood upon her breast without cleansing or confession invite generational curses upon themselves. Ask the elders of Jos and Plateau. Ask the farmers of Benue. Ask the oracles of Zangon-Kataf. The very land that gave Nigeria Gowon now bleeds under the sword he once unsheathed. Is this mere coincidence, or cosmic justice?

The evidence of spiritual fallout is undeniable. The regions and individuals most implicated in the war’s brutality—many from the Middle Belt and Northern command—have not prospered. Instead, they are torn by sectarian violence worse than anything before Biafra, overrun by Fulani herdsmen and jihadist gangs, engulfed in insecurity, poverty, and ethnic fragmentation.

Even General Gowon himself is but a shadow of the towering war hero once revered. His legacy is not peace, but a long echo of grief—and he knows it. Ask why no Nigerian leader has known peace since Biafra. Why coups, assassinations, and collapse have plagued the land like an unending plague. The blood still speaks.

Time is running out. The Bible warns: “Cursed is the one who perverts the justice due to the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow” (Deuteronomy 27:19). Nigeria has perverted justice against the Igbos—the strangers in their own land, the fatherless of war, the widows of genocide.

The spiritual hedge has been broken. Until the Igbo receive dignity, restitution, and honest national acknowledgment, this country will continue to devour itself. Until Gowon confesses, the spirit of the children of Biafra will haunt his generation—not with hatred, but with truth. And truth denied for too long becomes a consuming fire.

This is not a call for blood. It is a call for memory. A call for truth-telling. A call for a nation to look into the eyes of its own ghosts. Nigeria must not only remember the blood it spilled—it must atone. Only then can healing begin.

Let it be known: the Igbo do not seek vengeance. But the God of Abel, the Ala of the East, and the winds of justice—they remember. And until Nigeria kneels to acknowledge this, the blood will continue to speak.

Sylvester I. Onwudiwe, Esq., is a Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Nigeria and principal legal consultant to several international and local institutions.